THE HAZLETT HISTORIES are a series of deep dives into the history of the Pittsburgh area, with particular attention to the things most of us don’t hear about. It’s also a personal journey, as some of these topics make me examine my own place in the fabric of the Ohio Valley. This is history told from the corners.

It’s known as the Bulb, though I only had a dim awareness of it, likely absorbed from the ether of Pittsburgh Stuff constantly swirling on WQED in my childhood (and maybe still?). It was a well known feature of the landscape of Forest Hills, and Pittsburghers have a lot of feelings about it. It’s one of those things that people don’t think about for years until someone wants to do something to it and then the news finds out and everybody gets mad. The news is especially good at making people mad, and Pittsburghers are great at getting angry at things. One way to make Pittsburghers mad is to change something they remember.

I surveyed my Pittsburgh friends about it and got a smattering of memories and feelings about it. Most people recall it as a thing they saw once in a while, a building called the Bulb that had a history that some of them kind of knew about. Daria specifically recalled playing field hockey next to it, so close that some unlucky soul would occasionally have to jump the fence to retrieve the ball. Drew visited relatives who lived across the street from it. Jenda lives nearby. It’s a feature of the landscape of the city.

SMASH

Drew knew it also as the Westinghouse Atom Smasher, which is its lesser-known and proper name, and what a fantastic name it is! I admit to a fondness for anything with the word “Smasher” in it, but smashing atoms is quite a bit more interesting than other things one could smash, and I can’t think of smashing anything that might require an entire building be built for it (a building that smashes buildings is an intriguing thought, but I have never heard of a building smashing other buildings).

CHERNOBYL, BABY

Here’s a tangent, a wild twist of the steering wheel: the building built around the remains of the Chernobyl disaster. Rather than be a building that smashes, it’s a building that dismantles.

Chernobyl is at the top of mind lately because HBO made a TV show about it. I have issues with aspects of this otherwise exemplary telling of the tale [1] but it made everybody remember that little city and its misbehaving little nuclear reactor again. When Chernobyl had its tantrum, they capped it with concrete. That wasn’t enough to make the site as safe as it could be, so thus spawned a multi-year plan to cover it with another building. This building not only keeps the radiation in, but it has a whole system of pulleys and things to dismantle the reactor building within it. Slowly and carefully dismantling is like a slow and careful version of smashing, right? There it is: a building that smashes other buildings.

SMASH IT MORE

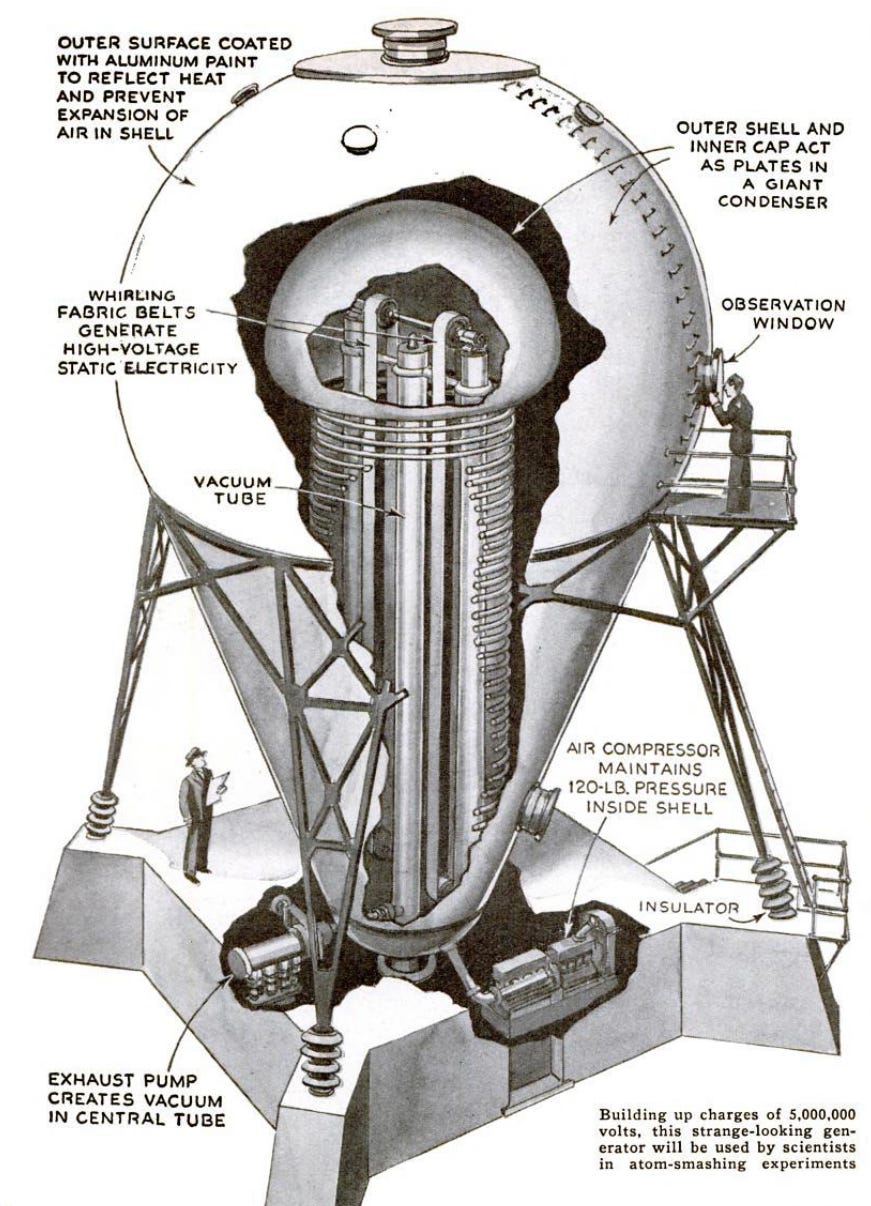

“Atom smashing” is a slightly overwrought word for the process, while also being factually correct. The bulb itself is mostly empty space provided for the amplification of pressure on the action happening in the center, as depicted in this wonderful illustration from Popular Science July 1937, which I would call the Golden Age of Thinking the Future Will Be Awesome.

The point of the Bulb, which houses a device known as a Van de Graaff Generator, was to generate a high voltage within the bulb of sufficient strength to propel a subatomic particle down a 47 foot tube, where it struck a target atom, smashing it apart. Without the bulb to cover the mushroom-shaped generator and tube, I imagine it would have been referred to by an altogether different name by creative Pittsburghers.

You might also know a Van de Graaff generator from your grade school classroom and that one girl with the really long hair who looked like a dandelion puff when she put her hands on it. Yep, that’s static electricity, which is the same stuff the Bulb used to smash atoms.

NUKES

The main purpose was to measure these reactions and to learn more about the nascent science of nuclear power generation. The bulb is credited with providing the evidence for photofission of uranium, a critical process in generating nuclear power. Unlike so many advances in the generation of nuclear power, the activities at the atom smasher were purely for civilian use, not military applications. I confess to a preference for technology designed to light peoples homes rather than obliterate them. The Ohio Valley has more to do with the history of nuclear power in the United States, but that will have to wait for Part 2.

WESTINGHOUSE!

Pittsburghers know that name, and probably lots of other people, too. It is the name of one of the biggest corporations in history, founded in 1886 by George Westinghouse, who was from Pittsburgh and started the company there. Westinghouse is no longer called that, having changed its name to the CBS Corporation after buying CBS and selling off everything that wasn’t connected to the whole broadcasting/entertainment thing. [2]

The Westinghouse I remember most clearly was the one David Letterman would complain about on his CBS show, as he railed against his corporate overlords. He had done the same thing at NBC, except the corporate overlord there was General Electric, Westinghouse’s biggest competitor (founded by George Westinghouse’s famous rival, Thomas Edison).

BULB, BABY

The current state, and recent history, of the Bulb are kind of a bummer. A reliable way to make Pittsburghers happy is to bring back something they forgot about. The Bulb rotted and fell over [3], as very old structures tend to do. There’s a group based in Tennessee, called the Early Model Particle Accelerator Corporation, that is raising money for the purpose of moving the Bulb elsewhere, refurbishing it, and using it for education purposes. It’s nice to think that the Bulb story might have a happy ending, though that ending will most likely not be in Pittsburgh. [4]

Irradiated humans are, in fact, not carriers of radiation that infect and continue to irradiate those around them after the initial exposure, a basic fact about radiation that a show otherwise extremely concerned with accuracy gets completely wrong.

This is kind of appropriate, as Westinghouse also started the first commercial radio station, also in Pittsburgh (KDKA) and radio itself was the closest Nikola Tesla got to his dream of broadcasting electricity. Tesla, as we all know, harnessed alternating current, which Westinghouse used to power dang near the whole country.

Technically, it was pushed over before it could fall.

You can donate and learn more at their website https://savethebulb.com/. The website reads like it was written by aliens who plan to use the Bulb for some nefarious purpose, but it was probably just written by engineers.

This is Atomic Pittsburgh part 1 — there will be at least two more, about the Shippingport Atomic Power Station and the fateful fate of Eben Byers.